I’m a bit of a knot head. I find knots fascinating. The most efficient ones are both useful and beautiful. A bit of filament, a bit of friction and voila — you have something that didn’t exist before. Security. A connection. A fabric, even.

If humans are the tool-making animal, knots were probably among the first tools we used. One reference I saw recently suggested that indeed knots predate humans — they were in use by pre-human hominids. So in tying knots, we connect ourselves with our deepest history on the planet.

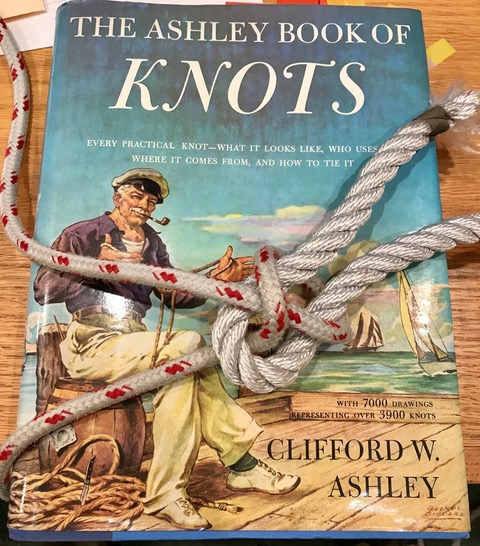

In the English-speaking world, the Bible of knots is a 1944 work that is both how-to and history, the Ashley Book of Knots, or ABOK. In it, Clifford Warren Ashley discusses nearly 4,000 knots and their uses. The book contains almost 7,000 of his illustrations, many of them numbered so they can be referenced by others.

That’s why today, pretty much any knot guide you find will refer back to Ashley. Animatedknots.com, for example, links to Ashley knots by ABOK number from most of its knot pages.

The Bowline

Ashley tells us that on square-riggers, the bowline (ABOK 1010) was the knot used to hold the “weather leech” of a square sail forward — toward the bow — to prevent it from backwinding.

Which is interesting, because today we use the bowline for essentially the opposite purpose — at the aft end of a sail — the jib to be specific. It’s the knot we often use to connect, or bend, the jib sheet onto the sail because it makes a non-slip loop that’s both easy to tie and easy to untie even after it’s been under tremendous tension.

So it makes some sense why the bowline is called that. But in sailing, as with any human undertaking worth the time, there is both ambiguity and mystery — and perhaps a bit of magic. We have a knot called a sheet bend. Why don’t we use that to bend a sheet onto a sail?

Actually, we do.

The Sheet bend

But we use the bowline to tie a jib sheet to the jib, right? Right. The weird thing is that the bowline is actually the same knot as the sheet bend, just in a different context. If you took a knife and cut the loop of a bowline, you’d still have a knot. But you’d have two lines, not one. The knot holding the two lines together — is a sheet bend (ABOK 1431).

You don’t have to cut your rope to prove this. Another way to prove is by way of what Ashley calls the Weaver’s knot (ABOK 485). As Ashley says, “In form, it is the same as the sheet bend but it is tied … in a distinctive way that I have seldom seen tied for any other purpose.” (P.78) Context is everything.

So you can tie a sheet bend the way a weaver would. To turn it into a bowline, just use the loose end of the rope you’re knotting to make a loop, instead of a separate line. Same process, same knot. Two different contexts, and thus two names. I’ll demonstrate this during our online chat about knots on May 7.

The same concept is true for several of the knots we all learned for our Basic Keelboat Sailing certification. Of the six required knots, three are actually the same knot, just in different contexts.

The Clove hitch and its friends

Tie a clove hitch (ABOK 1245) and look at it closely. You’ll see two lines next to each other held in place by a line diagonally across them.

OK, now let’s turn to the Round turn and two half hitches (ABOK 1720). Look at the two half hitches you tie to finish off the knot. If you tied them correctly, you have two lines next to each other held down by a diagonal across them. It’s a Clove hitch.

Same thing with the cleat hitch, (which, oddly, Ashley doesn’t directly mention, though he has an entire chapter on belaying and making fast to bollards, bits, pins and cleat-like devices).

We tie each of these three differently in those different contexts. And the name changes for each as a result. But they’re the same fundamental knot. As Ashley notes, “If a weaver himself tied the same formation in another way, the knot might bear another name.”

Oh, and a bit more mystery: The American Sailing Association emphasizes that the Clove hitch is an insecure knot. Don’t tie your boat to a dock with a clove hitch and expect it to still be secure when you come back from lunch. Indeed, the whole point of a Clove hitch is that it is easy to loosen and adjust. How ironic, then, that what ASA offers as a secure alternative, the Round turn and two half hitches, is secured by the same basic knot.

It gets more so: It takes only a slight twitch of the line to turn the “insecure” Clove hitch into a knot so secure it’s considered essentially impossible to untie if pulled too tight. Ashley says the Constrictor knot (ABOK 1188) “is one of the most difficult knots to untie and is not suitable for rope unless the purpose is a permanent one (such as a rope ladder).”