The South Bay Wreck and the Price of Good Navigation

Many South Bay sailors have seen the USS Thompson, better known as the South Bay Wreck. At low tide, it looks like a small apartment house halfway across the bay straight ahead after you pass under the power lines on the way to open water from Spinnaker Sailing.

The wreck has an interesting history, but the Thompson’s back story is where things turn fascinating for sailors and navigators hoping perfect their craft (and perhaps save their skins).

The USS Thompson was built at Bethlehem Iron Works in San Francisco in 1919, fitted out at Mare Island and launched in 1920. The vessel was part of a fleet of similar flush-deck California-based destroyers, performing sea patrol duties and taking on tasks like mapping the ocean bottom on the east and west approaches to the Panama Canal.

But by 1930, these so-called Clemson-class cruisers had become functionally obsolete. In addition to needing expensive refits, they exceeded allowed destroyer tonnage under a 1930 arms treaty. So, at the height of the Depression with funding tight, the decision was made to sell them for scrap for other uses. But that was years after the Navy had already unintentionally scrapped a big chunk of its fleet of its Clemson-class destroyers on the West Coast in one dramatic, terrifically ill-advised maneuver.

We’ll come to that later.

Meanwhile, after 10 years of largely unremarkable service, the disarmed hulk of the USS Thompson became a floating restaurant somewhere in the South Bay. Records are sparse about this period in the ship’s history but I have to imagine that restaurant must have been somewhere in the Redwood Creek estuary near Spinnaker Sailing because there’s nowhere else in South Bay where a ship of that size could approach land close enough to operate as a restaurant afloat.

In any case, food service wasn’t the end of the USS Thompson’s service to the country. In 1944, as the tide of World War II was turning and the United States built toward an invasion of Europe and was island-hopping toward Japan, the Navy re-acquired the Thompson for one last duty — as a practice target for bombardiers in training.

That’s how the South Bay Wreck came to its final place in the muddy shallows between Redwood City and Hayward.

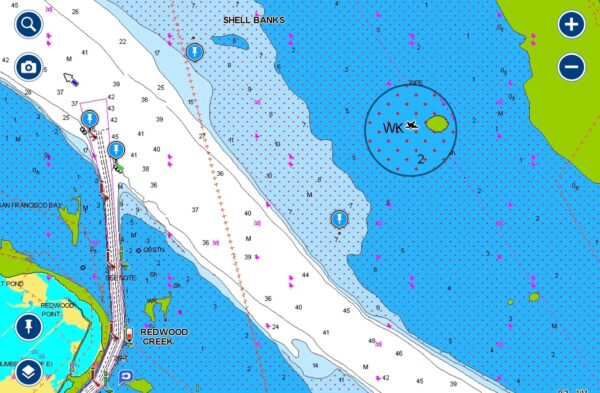

In the years since that ignominious nadir during World War II, the Thompson has enjoyed a bit more uplifting sort of renown. It’s prominently visible to pilots setting up for their final approaches to SFO or the San Carlos airport, for example. It’s become a destination for intrepid kayakers willing to brave the three-mile open-water paddle to visit. Geocachers have even placed a box of mementos there. (https://www.geocaching.com/geocache/GCRF24_uss-thompson?guid=37544836-06aa-4e31-9330-350fca97d8d6#cache_logs_table) and Spinnaker Sailing sailors all use it as a warning to not stray too far into the shallows.

The Thompson also provides Spinnaker Sailing’s navigation students an example of how a wreck visible above the waterline is indicated on nautical charts.

Interestingly, the Thompson isn’t the only ship the Navy intentionally sunk in and around San Francisco Bay. One of the Thompson’s sister Clemson-class destroyers, the USS Corry, rests in the mudflats of the Napa River upstream from Mare Island, where it was sunk to create a breakwater.

But those scuttlings weren’t the only ones the Navy performed on the Thompson and its sister ships — which brings us to the great Point Honda Disaster, the U.S. Navy’s largest loss of ships during peacetime.

The disaster is a tale of wounded ego, tragic miscalculation, faulty logic and fatal overconfidence. Also mixed in was misguided use, or non-use, of available navigational tools, including the relatively new radio direction finding system, that could have allowed the fleet’s navigators to avoid the disaster.

The toll: 23 sailors’ lives lost, seven destroyers sunk and two others damaged. Of the 14 naval vessels directly involved in the incident, only six, including the USS Thompson, escaped unscathed.

The story involved a fleet commander, Edward, H. Watson, who perhaps wanted to expunge perceived past errors with a record run from San Francisco to San Diego in foggy, hazardous conditions. Watson spent the trip apparently in deep conversation with a civilian guest he had invited aboard. Also implicated was the captain of Watson’s ship, Donald T. Hunter, who acted as the chief navigator for the squadron and who, as an officer with long experience, disdained the recently introduced coastwise radio direction system.

The scene was set — a fleet blinded by fog traveling at 20 knots, a speed that made use of depth sounders impossible, guided by leaders themselves blinded by issues distracting them from their duties.

Difficult wind and sea conditions placed the fleet far to the north and much closer to the California coast than Hunter believed possible. Fog had made updating visual fixes from lighthouses along the coast impossible. (The fleet’s last reliable fix was, ironically, from Pigeon Point Lighthouse on the San Mateo County coast, itself named for a long-ago shipwreck that claimed the clipper Carrier Pigeon.) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carrier_Pigeon_(ship)

The result was that 14 ships were steaming in single file each separated by about 300 yards from the ship ahead as they were attempting to make their way around Point Arguello and into the hazardous channel between the coast and the Channel Islands.

The same difficult conditions had already, only hours earlier, claimed the SS Cuba, a passenger ship that had gone aground on reefs off San Miguel Island, the western-most channel island. One of Watson’s ships, the USS Reno, had detached to rescue survivors of that wreck and thus wasn’t involved in the imminent disaster.

So, at a few minutes after 8 p.m. on Sept. 8, 1923, when Captain Hunter felt the USS Delphy slam full speed onto rocks, he assumed he had hit the same reefs as the Cuba. He urgently broadcast to other ships in the squadron to turn hard to port. But that was exactly the wrong instruction to make because in fact, due to his miscalculations, and his mistrust of navigational data he had access to, he hadn’t hit San Miguel Island, south of the channel entrance. He was actually aground 35 miles north of there on rocks that the Spaniards had centuries earlier named the Devil’s Jaw.

His instruction to turn to port aimed the ships following him right toward the rocky California coast.

Within minutes, in addition to the Delphy, the USS S.P. Lee, USS Young, USS Woodbury, USS Nicholas, and USS Fuller were irretrievably on the rocks, and their crews were fighting for their lives.

The USS Farragut, perceiving what was unfolding, managed to put all power astern and avoid the rocks, but only after being sideswiped by the Fuller fast on its way to its doom. The USS Percival and USS Somers narrowly avoided tragedy, though the Somers suffered serious damage. Next, the USS Chauncey, desperately trying to avoid the wreckage appearing out of the gloom dead ahead, got caught in an undertow and was shoved up alongside the Young, which had capsized. In that encounter the Young’s port propeller ripped open the Chauncey’s engine room, causing the Chauncey to lose all power before it, too, went aground.

In addition to the Percival, only the USS Kennedy, USS Paul Hamilton, USS Stoddert and our USS Thompson avoided becoming casualties in the disaster.

It’s interesting that a separate flotilla of Navy ships simultaneously heading to San Diego from San Francisco made the trip safely, its commander having chosen to restrict speed to 15 knots, which allowed navigators to access depth soundings in addition to other limited navigational data along the foggy coast.

Author Noah Andre Trudeau wrote a wonderfully detailed review of the disaster for Naval History Magazine. (https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2010/february/naval-tragedys-chain-errors) In it, he concludes, “At virtually any point along (the fleet’s) track from San Francisco to the jagged Honda cliffs some intervention might have changed the outcome, but there was none. In the end, we are left with the caution voiced by a naval officer who reviewed the case: ‘The price of good navigation is constant vigilance.’ “

Prudent sailors and wise navigators practice vigilance, maintain skepticism of both their tools and also their own conclusions, and invite critical review of their conclusions. We should all keep that in mind each time we put Redwood Creek astern under the watchful eye of our South Bay Wreck.

Wrecks at Point Honda: https://www.usni.org/sites/default/files/styles/hero_image_1600/public/NH%20109552.jpg?itok=zDCkAmuz

Wrecks at Point Honda: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/54/Point_Honda_wrecks%2C_vessel._-_NARA_-_295528.tiff

USS Corry: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/125749014576350806/